With the increasingly competitive environment to attract new clients – especially those with sizable portfolios available to manage – more and more advisory firms are beginning to spend money on their business development efforts. Either to engage in outbound marketing and advertising, to run “client appreciation events” that encourage existing clients to bring a friend to refer, developing relationships with centers of influence who can provide referrals… or just outright paying for referrals with upfront cash or ongoing revenue-sharing agreements.

The challenge, however, is that paying for referrals can potentially work too well – creating a conflict of interest for the referrer themselves, that may cause them to recommend the advisor regardless of how appropriate the fit is for the person being referred, or even the quality (or lack thereof) of the advisor themselves. Accordingly, the SEC instituted Rule 206(4)-3, which places relatively stringent regulatory requirements on solicitor relationships, from the disclosures that must be provided to potential clients, and the fact that solicitors themselves often must become "registered persons" as well.

In this guest post, compliance attorney Chris Stanley provides an in-depth look at the evolution of the SEC’s Solicitor Rule, the exact requirements for someone to qualify as a solicitor, what must be disclosed to prospective clients (and when, and how) when there is a solicitor arrangement, and the patchwork of state rules for determining when the solicitor themselves must also become registered as an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR).

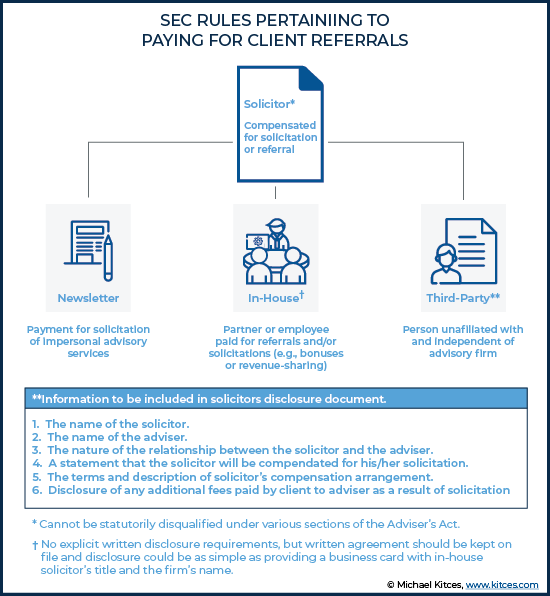

The starting point is simply to understand that the Solicitor Rule may apply anytime someone is paid for a referral and applies even if the person being referred doesn’t actually become a client (i.e., is only ever a prospect). In order to be a referrer, the individual must not already have a problematic regulatory history (e.g., no felonies or misdemeanors involving investments), and the arrangement itself must be commemorated into a written agreement (though the exact requirements vary depending on whether the solicitor is only for a newsletter or other “impersonal” advisory service, is an “in-house” solicitor of the firm, or is a third-party solicitor). In the case of third-party solicitors, in particular, substantial disclosure requirements also apply, in addition to providing the RIA’s Form ADV Part 2, at the time the solicitation occurs.

In the meantime, most states will also require that the solicitor themselves become registered as an IAR, potentially necessitating a Series 65 exam, though notably, even for SEC-registered investment advisers, it’s ultimately a state determination of whether the solicitor must become registered. Which means even for the same RIA, solicitors in some states may have to be registered, while solicitors in other states do not. The rules also sometimes vary depending on the type of solicitor, and some other professionals – e.g., attorneys and accountants – may have additional requirements (or prohibitions) for soliciting based on their own professional standards of conduct as well. In addition, state-registered investment advisers must also look to their individual states for guidance, as the entire framework of the Solicitor Rule 206(4)-3 itself is a federal rule for SEC RIAs, and doesn’t actually apply to state RIAs that must follow their own state’s rules instead.

Of course, the caveat to this all is that revenue-sharing agreements for referrals can actually be a very “expensive” way to market for new clients in the first place. Nonetheless, for those who want to engage in the practice, it is permitted for RIAs to pay solicitors to refer clients… but there are a number of specific rules that apply and additional disclosures that must be provided. And with a recent SEC Risk Alert highlighting the SEC’s concern that RIAs are not fully complying with the disclosure requirements, in particular, it’s especially important for firms that are using (or are considering the use of) solicitors to comply with the rules.

Chris Stanley is the Founder of Beach Street Legal LLC, a law firm and compliance consultancy that focuses exclusively on legal, regulatory compliance, and M&A matters for registered investment advisers and financial planners. He strives to provide simple, practical counsel to those in the fiduciary community, and to keep that community ahead of the regulatory curve. When he’s not poring over the latest SEC release or trying to meet the minimum word count for a Nerd’s Eye View guest post, you’ll find Chris enjoying the outdoors away from civilization. To learn more about Chris or Beach Street Legal, head over to beachstreetlegal.com.

Read more of Chris’ articles here.

The rules governing investment advisers’ ability to pay for client referrals may be deceptively complicated, but at least such rules exist in the first place.

When the SEC first proposed to regulate paid solicitors in Advisers Act Release No. 615 in 1978, it sought public comment on the advisability of an outright prohibition against such activity, because it was so “fraught with possible abuses” of an adviser’s fiduciary duty that it would constitute a fraud. The prohibition, either complete or subject to specified exceptions, would have intentionally stymied “the payment of referral fees of any kind or in any manner to a solicitor who is not an employee of the investment adviser."

Luckily, Advisers Act Release No. 615 offered an alternative: permit compensation for client solicitation and referrals, albeit subject to narrowly circumscribed conditions.

Between outright prohibition and regulated permissibility, the industry’s response was predictable. To use the SEC’s own words in the subsequent Advisers Act Release No. 688 when it adopted the “Solicitor Rule” as we know it today, “the overwhelming majority of commentators favored the regulation of cash referral fees."

Commentators analogized an adviser’s reasonable and disclosed cash referral fees to expenditures for marketing advertisements and other methods of developing new business. If banned, commentators argued that large investment advisers with in-house marketing staff would have an unfair advantage over smaller advisers that needed to rely on independent professionals to solicit new clients, and smaller advisers would be further disadvantaged relative to banks, insurance companies, and broker-dealers who would not be subject to the ban. To a certain extent, permitting paid client solicitations and referrals was seen as a way to even the playing field for smaller advisers and avoid what could otherwise be anti-competitive consequences to banning such practices altogether.

The public spoke, the SEC listened, and the new SEC Rule 206(4)-3 (the “Solicitor Rule”) was adopted in 1979.

Let’s get a few things straight right out of the gate for purposes of the SEC’s Solicitor Rule 206(4)-3 in terms of what constitutes a “solicitor” in the first place:

A “solicitor” means any person who, directly or indirectly, solicits any client for, or refers any client to, an investment adviser.

Soliciting a client and referring a client are often used interchangeably, but they are actually distinct activities. To “solicit” is to engage in sales activity to try to encourage a client to work with an adviser. To “refer” is to introduce a client to an adviser, even if the solicitor does not convince, encourage, or recommend the adviser.

Indeed, in the Adopting Release, the SEC noted that “a person could be a solicitor within the meaning of the rule if he supplies the names of clients to an investment adviser, even if he does not specifically recommend to the client that he retain that adviser [because a referral alone is sufficient to trigger solicit status even if it is not a full-borne solicitation itself].”

It is worth mentioning, however, that the SEC has issued a few No-Action letters over the years that carve-out adviser referral programs sponsored by membership associations that met certain criteria (see, e.g., International Association for Financial Planning [June 1, 1998] and National Football League Players Association [January 25, 2002]). The basic concept is that the IAFP (now the Financial Planning Association) and NFL Players Association established a referral program through which potential advisory clients could seek and obtain a list of advisers from which they could subsequently seek advisory services. In both cases, the Solicitor Rule was found not to apply.

The title of the Solicitor Rule is actually “Cash payments for client solicitations.” The use of “cash” is intentional, as a solicitor must actually be compensated with cash for a solicitation or a referral to apply, and the Solicitor Rule does not apply if there is no cash payment (or there is a noncash payment) to solicitors.

But don’t get too cute here; just because an adviser doesn’t pay a solicitor in fat stacks of dollar bills doesn’t mean there aren’t potential conflicts of interest to be disclosed. One such conflict of interest the SEC was (and continues to be) particularly concerned about are client referrals that may be made by a broker-dealer to an adviser in exchange for the adviser directing brokerage transactions to that broker-dealer. This practice creates potential best execution concerns that are beyond the scope of this article, but suffice to say that an investment adviser that confers something of value other than coin to a solicitor should still ensure it is adhering to appropriate fiduciary obligations and disclosure expectations for solicitors (and recognize that solicitor status has likely been triggered in the first place).

A solicitor is not necessarily a third-party independent of an adviser’s own personnel. A solicitor can also be (i) a partner, officer, director or employee of an investment advisory firm, or (ii) a partner, officer, director or employee of a person which controls, is controlled by, or is under common control with, the investment adviser.

In other words, there are “in-house” solicitors, and there are “third-party” solicitors. Both are covered by the Solicitor Rule, albeit with different regulatory expectations (as will be explained further below).

A “client” (the person being solicited, who triggers the rule and to whom disclosures are due) includes not just those who sign on to become clients, but any prospective client as well.

What this essentially means is that a paid solicitation or referral that does not result in the solicited or referred person actually becoming a client of the adviser would still trigger the requirements of the Solicitor Rule as a prospective client. In other words, even unsuccessful solicitations and referrals still count if cheddar (i.e., compensation) changes hands for that solicitation or referral, and thus requires the rules to be met and the associated disclosures (as discussed further below) to be provided.

The Solicitor Rule, as written under Rule 206(4)-3 of the Advisers Act, technically only applies to federally-registered investment advisers (i.e., SEC-registered investment advisers), not to state-registered investment advisers.

However, as discussed later in this article, there are myriad state solicitor rules that need to be accounted for by both state- and federally-registered advisers.

With this backdrop, let’s dive into what the Solicitor Rule actually requires.

In order for an advisory firm to pay either an in-house or third-party solicitor, the solicitor must not be “statutorily disqualified” from receiving compensation for acting as a solicitor. That is, the solicitor must not be a person:

In short, the solicitor can’t (already) be a regulatory troublemaker, and a solicitor who gets into regulatory trouble may cause the termination of his/her solicitor eligibility.

Assuming the solicitor isn’t a regulatory troublemaker, cash payments for client solicitations may only be made pursuant to a written agreement, to which the adviser and the solicitor are both parties, and are still prohibited unless they are made pursuant to one of three specific scenarios (i.e., three different types of RIA solicitor arrangements):

Newsletters and other Impersonal Advisory Services. The first permitted scenario for cash payment of solicitor fees is one in which a solicitor solicits clients only for the provision of impersonal advisory services by the adviser. Impersonal advisory services means “investment advisory services provided solely by means of (i) written materials or oral statements which do not purport to meet the objectives or needs of the specific client, (ii) statistical information containing no expressions of opinions as to the investment merits of particular securities, or (iii) any combination of the foregoing services.”

The illustrative example of impersonal advisory services used by the SEC in its adopting release was a newsletter that a prospective client could purchase, instead of receiving specifically-tailored asset management services. Advisers can, therefore, pay solicitors to drive potential clients to the adviser’s website, blogs posts, educational workshops, investment newsletters, etc., assuming no specifically-tailored advice is conveyed by such means. (But solicitor agreement requirements and disclosure rules still apply, as the rules are merely stating that such arrangements can be paid solicitor arrangements in the first place.)

In-House (Employee) Solicitors. The second permitted scenario encompasses cash payments to: (i) “in-house” solicitors (e.g., a partner, officer, director or employee of an adviser); or (ii) a partner, officer, director or employee of a person which controls, is controlled by, or is under common control with the adviser.

This means that, technically speaking, if any of an adviser’s partners, officers, directors, or employees (directly or by affiliation) are to receive cash compensation from the advisory firm for client solicitations or referrals (e.g., business development “bonuses” or internal revenue-sharing agreements for bringing in new clients), there should be a written agreement on file between the investment advisory firm and each such in-house solicitor.

At least for in-house solicitors, though, there are no explicit requirements from the SEC of what such an agreement must contain. Thus, conceptually, this written agreement could simply be a signed employment offer letter or employment agreement itself that describes the nature of the in-house solicitor’s revenue-sharing, bonus, or other compensation for his or her client generation activities.

In addition, if an advisory firm wants to provide cash incentivization to employees to refer new clients to the firm, the employee must disclose to the prospective client his or her status as a partner, officer, director or employee of the adviser (or the nature of any affiliation with the adviser). Technically, this status/affiliation disclosure need not be in writing, but the old regulatory adage, “If it isn’t in writing, it never happened,” is hard to completely ignore. Providing something as simple as a business card with the in-house solicitor’s title and the firm’s name should suffice in this regard, though.

Third-Party Solicitors. The third permitted scenario is where the rubber really meets the road for most referral and solicitation arrangements because it is in this scenario that third-party solicitors finally come into the fold.

In fact, if the person receiving cash for client referrals or solicitations is independent of and unaffiliated with the adviser, four additional requirements kick in.

The first additional requirement is that the written agreement between the third-party solicitor and the adviser must contain the following specific elements:

The second requirement when it comes to third-party solicitors is that the advisory firm itself (not just the third-party solicitor) receives from the solicited client a signed and dated acknowledgment of receipt of the adviser’s Form ADV Part 2 brochure and the separate solicitor’s disclosure document at or before entering into an advisory agreement with such solicited client.

The third requirement is that the investment advisory firm makes a bona fide effort to ascertain whether the third-party solicitor has complied with his/her agreement with the adviser, and has a reasonable basis for believing that the third-party solicitor has so complied. The RIA doesn’t have to supervise a third-party solicitor to the same degree that it would its own employee (as the SEC’s original proposal would have first required!), but the firm still must make a “bona fide effort” to ascertain whether or not the third-party solicitor is abiding by the agreement he or she signed.

So what constitutes a “bona fide effort”? In the adopting release, the SEC suggests that it would involve, at a minimum, making inquiries of some or all solicited clients in order to ascertain whether the third-party solicitor has made improper representations or has otherwise violated the agreement with the adviser. This creates a potentially awkward conversation with solicited clients (“Hey, client, did that guy who referred you to me breach an agreement you’ve never seen?”), but alas that is the sole example the SEC provided. Annual certifications of compliance signed by third-party solicitors seem like a more realistic means to demonstrate a “bona fide effort.”

The fourth and final requirement relates to the separate written solicitor’s disclosure document that must be provided to all solicited clients alongside the ADV Part 2 brochure. Specifically, the solicitor’s disclosure document must include:

The specificity with which the third-party solicitor’s compensation must be described cannot be overstated. If the third-party solicitor is to be paid a flat fee, the actual flat fee amount must be included. If the third-party solicitor’s fee is based on a percentage of the solicited client’s assets under the adviser’s management or the adviser’s advisory fee over some time period (or indefinitely), the percentage and (indefinite or other specified) time period must be included. If the third-party solicitor’s compensation is deferred until some later milestone is achieved, such terms must also be included.

Notably, it is these third-party solicitor arrangements (and the delivery of accompanying disclosure documents to the solicited prospect) that advisers seem to be screwing up the most, at least as far as the recent October 31, 2018, SEC Risk Alert on the Cash Solicitation Rule contends. The most common deficiencies stemmed from inadequacies related to the solicitor’s agreement, the solicitor’s disclosure document, client acknowledgments, and the bona fide effort to ascertain third-party solicitor compliance. Specifically, the SEC found that (i) solicitor agreements did not exist or did not contain the specified provisions, (ii) solicitor disclosure documents did not exist, were not provided to solicited clients, or did not contain the specified provisions, (iii) client acknowledgements were not received at all, were not received in a timely fashion, or were not signed/dated, and (iv) advisers could not describe any efforts they took to ascertain third-party solicitor compliance.

Oh, and in case it isn’t obvious, an adviser should retain its solicitor-related documents in its books and records and expect the SEC to request them during an exam.

It is worth pausing here to reinforce the fact that everything discussed above is applicable to SEC-registered advisers and their solicitors, but not necessarily to state-registered advisers and their solicitors. While states may defer to the SEC with respect to certain rules and regulations (like custody, e.g.), solicitation of clients is an activity upon which a lot of states have imposed their own unique regulatory framework. From this point forward in the article, the added complexities of state regulation will be brought into the fold.

Everything discussed in this article so far has addressed the federal cash solicitation rule as it applies to investment advisers (registered with the SEC). But what about the solicitors themselves? If and when do they need to take the Series 65 and/or become registered as an investment adviser representative? This is where it gets messy.

As a fundamental matter, it is important to highlight the fact that the SEC does not register or license natural persons (including solicitors) associated with SEC- or state-registered investment advisers, or require their qualification by examination (e.g., the Series 65). Registration, licensing and qualification requirements of such persons have been delegated to the states (with one important exception applicable only to SEC-registered advisers and their “supervised persons” as discussed below).

Thus, in practice, whether a solicitor must become registered as an investment adviser representative with a particular state depends on both the activity of the solicitor, his or her relationship to the RIA, and the particular state(s) involved and their view on the registration of solicitors operating in their state.

Because Federalism, each state has adopted its own rules and regulations that govern the licensing, registration, and qualification of investment adviser representatives (as such term is defined by a particular state).

Most states specifically include solicitation activity as an activity that requires some combination of licensing, registration, and qualification as an investment adviser representative. This could entail, for example, passing the Series 65 exam (or qualifying with a professional exemption like the CFP marks or CFA designation), registering as an IAR of an existing RIA and filing a U4, or registering a new RIA through which to engage in solicitation and referral activity for compensation. The NASAA Uniform Securities Act (which many states have adopted either in full or in part) defines investment adviser representative as one who, among other activities, “solicits, offers, or negotiates for the sale of or sells investment advisory services” (effectively requiring any solicitor doing business in that state to register an IAR of an RIA).

However, not all states consider either in-house or third-party solicitors to be investment adviser representatives (as defined by the particular state), or otherwise require licensing/registration of in-house or third-party solicitors.

Missouri, for example, very explicitly does not require solicitors to register as investment adviser representatives. (See FAQ #7: “Q: Do solicitors for investment advisers have to be registered? A: NO. Investment advisers may pay cash fees to a solicitor who refers business as long as the solicitor does not offer investment advice and is not subject to disqualification. The fee must be paid pursuant to a written agreement between the adviser and the solicitor and a copy of this agreement must be given to the client prior to any advisory contact.”)

California, on the other hand, requires solicitor registration as an investment adviser representative but does not necessarily require that the solicitor qualifies as such by taking the series 65. (See 10 CCR § 260.236(c)(2), which states that qualification requirements do not apply to “any investment adviser representative employed by or engaged by an investment adviser only to offer or negotiate for the sale of investment advisory services of the investment adviser.”)

North Carolina effectively eliminates the entire concept of third-party solicitors and requires solicitors to register as investment adviser representatives with the RIA for which they are soliciting. In other words, all solicitors to North Carolina RIAs must be in-house solicitors and registered/supervised accordingly.

Georgia excludes CPAs and attorneys licensed in Georgia that solicit their own pre-existing accounting or legal clients on behalf of an RIA from the definition of investment adviser representative, and also has what amounts to a “de minimis” threshold that permits any other Georgia resident to solicit on behalf of an RIA so long as the annual clients solicited is capped at ten (see Rule 590-4-4-.12(2)).

New Mexico exempts solicitors from registering as investment advisers or investment adviser representatives so long as such solicitors only receive a one-time payment in consideration for the solicitation activity (see FAQ #2).

Texas is an example of a state that clearly distinguishes between solicitors to state-registered advisers, and solicitors to SEC-registered advisers, as well as in-house and third-party solicitors. Per FAQ 1.B.3 and 1.B.4: Q: “I am operating in Texas as a solicitor for an SEC-registered investment adviser. Must I also register or make a filing with the Texas Securities Commissioner? A: As a general rule, if a solicitor is a supervised person, the solicitor is not required to register with the Texas Securities Commissioner. Whether a solicitor for an SEC-registered investment advisor is subject to state registration requirements turns on: (1) whether the solicitor is a supervised person, (see FAQ 1.B.1) and (2) whether the solicitor is an [investment adviser representative] (see FAQ 1.B.2). If a solicitor of an SEC-registered investment adviser does not provide investment advice, the solicitor is not required to register with the Texas Securities Commissioner, but is subject to the fee and notice filing provisions. A third-party solicitor for an SEC-registered investment adviser (i.e., a solicitor who is not an employee of the adviser) is not a supervised person and, therefore, has to register with the Texas Securities Commissioner. A solicitor who solicits on behalf of both a Texas-registered investment adviser and an SEC-registered investment adviser is subject to Texas registration requirements.” “Q: I am operating in Texas as a solicitor for a Texas-registered investment adviser. Must I also register or make a notice filing with the Texas Securities Commissioner? A: A solicitor of a Texas-registered investment adviser must register with the Texas Securities Commissioner and meet all state registration requirements contained in the Act and Rules.”

Note, however, that Texas still requires in-house solicitors to SEC-registered advisers to pay a fee and notice file in the state. Technically, paying a fee and notice filing are not the same as “licensing, registration, or qualification,” which can be preempted (as discussed in the next section). Texas uses similar logic when it comes to its implementation of the national de minimis standard, but that’s for another article.

The point is that state rules and regulations can vary dramatically and should be reviewed carefully in nearly every solicitor use case. This can be a lot of states, because registration may be driven not only by the state(s) where the RIA is located and does business, but also the state(s) where any of the RIA’s solicitors are located. And as noted above, the rules in each of those states may not be the same. Case in point, state solicitor rules can differ based on whether the solicitor is a natural person or entity, whether the solicited client is a natural person or entity, whether the solicitor is soliciting investments into a private fund, whether the state requires dual-registration of third-party solicitors, and so on and so forth.

It’s a cruel paradox that smaller, state-registered advisers with fewer resources – especially those that are required to be registered in multiple states – are often subject to a more convoluted web of dense statutes, conflicting requirements, and in some cases even unwritten interpretations by their regulatory overlords. (Just wait until state-by-state fiduciary rules get layered on top… and now I will step down from my soapbox.)

Notwithstanding the general rule that at least most states will require solicitors to qualify and/or register as IARs (albeit with some variability on a state-by-state basis), there is an important exception to the rule: no state can impose its own registration, licensing, or qualification requirements on “supervised persons” (including in-house solicitors) if such persons (a) are not considered to be “investment adviser representatives” of an SEC-registered adviser, or (b) do not have a “place of business” in such state. In other words, non-advisor employees of SEC-registered firms who don’t actually have/work with their own client generally do not need to be registered with a state as (in-house) solicitors, even if they are compensated to refer/bring in clients to the firm.

The legal basis for this federal preemption can be found in the National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 1996 (commonly referred to as “NSMIA”): “No law of any State or political subdivision thereof requiring the registration, licensing, or qualification as an investment adviser or supervised person of an investment adviser shall apply to any person (A) that is registered [with the SEC], or that is a supervised person of such person, except that a State may license, register, or otherwise qualify any investment adviser representative who has a place of business located within that State.”

It’s critical to understand a few federal definitions to unwind this narrowly-tailored federal preemption:

The long and short of it is that in-house solicitors to SEC-registered advisers cannot be subject to any state’s licensing, registration, or qualification requirements if they do not fall under the federal definition of investment adviser representative, or do not have a place of business in the particular state.

If an in-house solicitor to an SEC-registered adviser is considered an investment adviser representative under the federal definition, the solicitor must next look to state rules and regulations to assess licensing, registration, and qualification requirements. Which, as discussed earlier, will generally require registration as an IAR of the SEC-registered Investment Adviser.

Overall, this means that unless a solicitor is in-house with an SEC-registered adviser and is not considered to be an investment adviser representative as defined above, state-by-state licensing, registration and qualification requirements are almost always going to come into play (either by requiring the solicitor to register, or by triggering the solicitor’s status as an IAR which in turn would require them to register anyway). Similarly, such state-by-state requirements are going to come into play for nearly all third-party solicitors to SEC-registered advisers, as well as all in-house and third-party solicitors to state-registered advisers.

Like the state-by-state web of rules and regulations imposed on solicitors themselves, the regulatory landscape for state-registered RIAs that retain such solicitors is similarly varied, as Rule 206(4)-3 of the Investment Advisers Act technically only applies to SEC-registered firms. States that oversee state-registered investment advisers ultimately set their own state rules for firms registered in their states. And since there are 50 states, that unfortunately creates the potential for a lot of different rules for state-registered firms depending on which (and how many) of the 50 states they’re registered in!

The North American Securities Administrators Association (“NASAA”) attempted to facilitate some degree of uniformity, however, by issuing a proposed Model Rule in 2009 regarding solicitors in the form of Uniform Securities Act of 1956 Model Rule 401(g)(4)-1 and Uniform Securities Act of 2002 Model Rule 404(a)-2. The proposed Model Rule largely tracks the Federal Rule’s statutory disqualification definition, requires the same written solicitor agreement and client acknowledgment, and imposes the same bona fide compliance effort. But it differs from the Federal Rule in at least two important ways: the proposed Model Rule (1) generally requires any solicitor to register as an investment adviser representative of an RIA, and (2) does not limit its applicability to cash payments, but instead broadens its applicability to “any other economic benefit” conferred to the solicitor.

The challenge, though, is that the proposed Model Rule is just that… a model of a proposed rule that states can adopt. It isn’t automatically the rule in every or any state, especially since NASAA has not adopted the rule itself. And even if NASAA ever does adopt the rule, it must still in-turn be adopted by each/every particular state, before it becomes enforceable in that state. Accordingly, state-registered RIAs must still, therefore, defer to their particular state(s)’ specific rules and regulations with respect to their use of solicitors.

In the meantime, some states do plainly defer to the Federal Rule via cross-reference (like Georgia, which does so indirectly through its recordkeeping rule: Rule 590-4-4-.14), others impose their own unique requirements (like North Carolina’s 18 NCAC 06A .1717, which still basically mimics the Federal Rule in many respects), and still others are largely silent with respect to the use of solicitors altogether (like New York, which is an outlier in a lot of other respects as well).

The key point, though, is that all, none, or some elements of the Federal Rule may be applicable to state-registered RIAs that have engaged solicitors. So in addition to determining what solicitors may be required to do in any state in which they have a place of business, state-registered investment advisers themselves must look to their own state’s rules to determine what is expected of them with respect to solicitors as an RIA registered in that state. Regardless of what Rule 206(4)-3 requires (or not) of SEC-registered investment advisory firms.

If you’re an RIA interested in paying a solicitor to refer clients to the firm (or are interested in receiving cash for referring clients to other advisers as a solicitor), consider the following compliance recommendations:

Solicitor compliance obligations, like many compliance obligations, can be frustratingly complicated and layered with nuance that isn’t readily apparent on the surface. Yet given the SEC’s recent attention to solicitor compliance (as highlighted in its aforementioned Risk Alert) and anecdotal focus I’ve seen from state regulators both during initial registrations and subsequent exams, advisers should expect continued scrutiny in this area for the foreseeable future.

Quality? Nerdy? Relevant?

We really do use your feedback to shape our future content!